SAF Policy Around the World

Contributed by Adam Klauber

Government policy can be instrumental in advancing sustainable aviation fuel (SAF), especially when market forces alone are slow to drive adoption. SAF, which can significantly reduce aviation emissions, currently accounts for only about 0.3% of global jet fuel. Cost, feedstock availability, and infrastructure timelines are major barriers to demand and supply. Many governments around the world are stepping in with policies to accelerate SAF production and adoption.

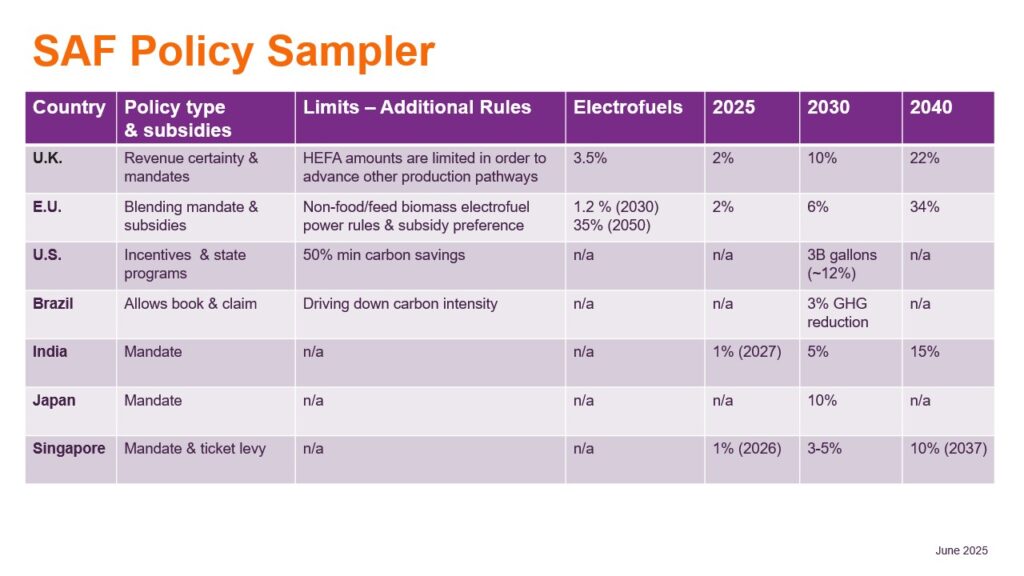

These SAF policies reflect different governmental systems and priorities. Comparing them can help producers, developers, and investors make decisions for the near term and try to influence future government actions. This chart summarizes some key SAF policies around the world. You’ll find more details below, with some of the most interesting aspects of these policies highlighted.

United Kingdom: Mandates + Revenue Certainty

For a small country, the United Kingdom has a very strong policy, combining incentives — in the form of high credits for carbon reduction — with mandates for SAF reaching 10% of forecasted jet fuel consumption by 2030. This is an ambitious target, given that the UK’s current SAF supply is near zero. The timeline aligns with the time needed to build SAF plants, hopefully encouraging rapid project development.

The UK is especially interesting because it is also developing a revenue certainty model. If airlines can’t afford SAF due to market conditions, the government can provide financial support to cover the price premium. Having a government backstop to cover the price premium of SAF is unique to the UK right now.

The UK is also trying to support new SAF feedstock technologies such as electrofuels by scaling down the percentage of HEFA SAF (the most mature SAF production pathway today) that can be used to meet mandates. The HEFA process can account for 100% of SAF through 2026, after which the allowed share progressively drops to 71% in 2030 and 35% in 2040. Regardless of production pathway, SAF must meet a 40% carbon reduction threshold compared to fossil jet fuel to qualify under the mandate.

More on UK SAF policy can be found here.

European Union: Blending Mandate + Subsidies

The ReFuelEU blending mandate obligates fuel suppliers to blend increasing amounts of SAF into jet fuel. It started modestly at 2% in 2025 but rises to 34% by 2040 and ultimately 70% by 2050. The EU uses percentage-based blending targets tied to actual fuel usage, which demands detailed data calculations that may make it harder to implement.

Eligible SAF must meet a wide set of feedstock and emissions reduction requirements set out in the Renewable Energy Directive (RED). EU SAF must achieve emissions reductions of at least 65% compared to fossil fuel, with carbon intensity values to decrease over time.

The EU recently announced a subsidy program to help airlines afford SAF. They can receive subsidies of up to €6 per liter for electrofuels and €0.5 per liter for biofuels. In addition to offering higher subsidies, EU policy aims to advance newer technologies like electrofuels and alcohol-to-jet (ATJ) fuel with a specific prohibition on recognizing imports of HEFA. But the EU needs to rely on outside supply to reach its targets due to the realities of how much feedstock can be grown or obtained from the region, so the policy may have to allow for Book & Claim contracts to satisfy requirements.

More on EU SAF policy can be found here.

United States: Incentives

The United States bears extra attention due to its status as a leading supplier of SAF and its unique policy profile. Rather than using mandates, the United States relies on tax incentives and voluntary programs to stimulate domestic production of SAF. After recent revisions, the 45Z producers tax credit now in place through 2029 offers up to $1.00 per gallon for SAF, depending on feedstock emissions profiles.

In the United States and elsewhere, Scope 3 customers — typically corporations seeking to reduce Scope 3 aviation emissions — are increasingly entering the SAF market, helping to cover costs and drive demand and investment. With SAF certificate insets, these companies can buy the environmental attributes of SAF and apply them against their aviation emissions, while the fuel itself goes into the supply chain. The Book & Claim chain-of-custody model tracks these transactions and ensures integrity.

Although US policy has fluctuated, it’s important to recognize the existing federal Renewable Fuel Standard (RFS) has remained stable, with no expiration. In fact, recent EPA proposals have better aligned RFS obligations and targets with real-world production capacity. That’s a strong signal to producers that some form of market-sensitive government incentive will exist over the duration of their investment. SAF must deliver at least 50% life-cycle GHG reductions to qualify.

Several states also offer SAF incentives. California’s Low Carbon Fuel Standard (LCFS) is opt-in and voluntary, rewarding low-carbon fuel production with tax credits without mandating the use of specific fuels. States like Washington, Oregon, New Mexico, Illinois, and Iowa have also introduced SAF-specific tax benefits.

The US incentive model can avoid economic distortions that sometimes accompany mandates, when the penalty for noncompliance can easily become the price of the product, regardless of what it costs to produce. This can stifle demand and put producers out of business.

In an incentive market, risk comes in times of volatility or high prices, when it can be difficult for customers or producers to manage the costs. But overall, the price of incentive-driven SAF is closer to the real cost of producing it, which is more efficient for buyers.

More on US SAF policy can be found here.

Brazil: Emissions-Based Targets + Book & Claim

Brazil’s Fuel of the Future policy takes a pragmatic approach to aviation decarbonization. First, it focuses on GHG reductions, not SAF volume. Airlines must reduce domestic aviation emissions by 3% by 2030 and 10% by 2037 based on a full life-cycle analysis. This approach incentivizes the use of technologies or feedstocks with lower carbon intensities and the continual improvement of SAF over time.

Second, Brazil is the only country explicitly allowing Book & Claim for SAF. Airlines may be able to meet emissions targets by purchasing SAF attributes tied to fuel used elsewhere. For some period of time, that may be the way they can comply because there isn’t yet commercial SAF supply in Brazil.

More on Brazil SAF policy can be found here.

India: Mandate

India targets 1% SAF on international flights by 2027, rising to 2% in 2028, with domestic SAF targets expected later. It’s one of the few developing countries with such a policy. India is attracting considerable interest from investors, especially in the alcohol-to-jet and ethanol conversion technologies, which can be supported by an array of local feedstocks, including bamboo and sugarcane. Some SAF production plants are in the pilot or ramp-up stage, including ethanol producer Praj and state-controlled refiner IOC, which has projected 1% SAF production on its own by fall 2025.

However, it’s not yet clear whether the domestic demand from airlines and corporations will be sufficient to cover the price premium. This challenge may lead some SAF producers to sell their physical supply to more developed markets, where there is a higher willingness to pay.

More on India SAF policy can be found here.

Japan: Preparing for a 2030 Mandate

Japan mandates that refiners replace 10% of fossil jet fuel with SAF by 2030. Though the mandate is not yet in force, preparations to comply are underway. Government subsidies of up to ¥30 per liter ($0.78 per gallon) are available for producers and are already being awarded. Some airlines are signing offtake agreements. And one refinery began delivering SAF domestically in early 2025, although its production volumes are unclear.

More on Japan SAF policy can be found here.

Singapore: Mandate + Passenger Fee

Beginning in 2026, flights departing Singapore must use 1% SAF, ramping to 3%–5% by 2030. The mandate will be supported by a centralized SAF procurement system and a levy on ticket prices, shifting the cost burden from fuel producers to passengers. The levy varies by target volumes of SAF, its cost, and the distance and class of travel.

The policy is intriguing because it allows for the influence of market forces. Money collected from the levy will purchase fuel at competitive prices, which avoids market distortions and shields airlines.

One short-term issue in Asia is limited regional demand, given the delayed mandate timeframe. For example, Singapore currently exports SAF to the UK. A global Book & Claim system could allow SAF certificates to fulfill international mandates without physically transporting fuel — minimizing emissions and costs.

More on Singapore SAF policy can be found here.

Conclusion: The Need for Long-Term Policy Certainty

Government policies worldwide are providing material support and signaling confidence in future SAF development. This article is by no means an exhaustive list, and additional SAF policies are continually coming into play. But regardless of where SAF programs are enacted, the question of policy certainty stands out.

Giving private investors and entrepreneurs confidence that government frameworks that exist today will exist well into the future is probably the number one way to unlock new supply. Financial institutions ignore short-term policy for capital investment decisions and weigh permanent measures like the US Renewal Fuel Standard most favorably when determining policy risk and commercial viability.

Policy stability, ideally aligned with investment timelines, is a key goal for the SAF industry and its supporters to pursue in the interest of decarbonizing aviation while meeting the enduring demand for flight.